Spy Tech: The NRO and Apollo 11

When you think of “secret” agencies, you probably think of the CIA, the NSA, the KGB, or MI-5. But the real secret agencies are the ones you hardly ever hear of. One of those is the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO). Formed in 1960, the agency was totally secret until the early 1970s.

If you have heard of the NRO, you probably know they manage spy satellites and other resources that get shared among intelligence agencies. But did you know they played a major, but secret, part in the Apollo 11 recovery? Don’t forget, it was 1969, and the general public didn’t know anything about the shadowy agency.

Secret Hawaii

Captain Hank Brandli was an Air Force meteorologist assigned to the NRO in Hawaii. His job was to support the Air Force’s “Star Catchers.” That was the Air Force group tasked with catching film buckets dropped from the super-secret Corona spy satellites. The satellites had to drop film only when there was good weather.

Spoiler alert: They made it back fine.

In the 1960s, civilian weather forecasting was not as good as it is now. But Brandli had access to data from the NRO’s Defense Meteorological Satellite Program (DMSP), then known simply as “417”. The high-tech data let him estimate the weather accurately over the drop zones for five days, much better than any contemporary civilian meteorologist could do.

When Apollo 11 headed home, Captain Brandli ran the numbers and found there would be a major tropical storm over the drop zone, located at 10.6° north by 172.5° west, about halfway between Howland Island and Johnston Atoll, on July 24th. The storm was likely to be a “screaming eagle” storm rising to 50,000 feet over the ocean.

In the movies, of course, spaceships are tough and can land in bad weather. In real life, the high winds could rip the parachutes from the capsule, and the impact would probably have killed the crew.

What to Do?

Brandli knew he had to let someone know, but he had a problem. The whole thing was highly classified. Corona and the DMSP were very dark programs. There were only two people cleared for both programs: Brandli and the Star Catchers’ commander. No one at NASA was cleared for either program.

With the clock ticking, Brandli started looking for an acceptable way to raise the alarm. The Navy was in charge of NASA weather forecasting, so the first stop was DoD chief weather officer Captain Sam Houston, Jr. He was unaware of Corona, but he knew about DMSP.

Brandli was able to show Houston the photos and convince him that there was a real danger. Houston reached out to Rear Admiral Donald Davis, commanding the Apollo 11 recovery mission. He just couldn’t tell the Admiral where he got the data. In fact, he couldn’t even show him the photos, because he wasn’t cleared for DMSP.

Career Gamble

There was little time, so Davis asked permission to move the USS Hornet task force, but he couldn’t wait. He ordered the ships to a new position 215 nautical miles away from the original drop zone, now at 13.3° north by 169.2° west. President Richard Nixon was en route to greet the explorers, so if Davis were wrong, he’d be looking for a new job in August. He had to hope NASA could alter the reentry to match.

The forecast was correct. There were severe thunderstorms at the original site, but Apollo 11 splashed down in a calm sea about 1.7 miles from the target, as you can see below. Houston received a Navy Commendation medal, although he wasn’t allowed to say what it was for until 1995.

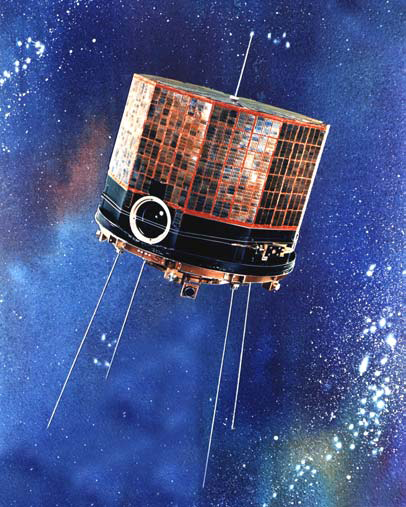

In hindsight, NASA has said they were also already aware of the weather situation due to the Application Technology Satellite 1, launched in 1966. Although the weather was described as “suitable for splashdown”, mission planners say they had planned to move the landing anyway.

youtube.com/embed/iZKwuY6kyAY?…

Modern Times

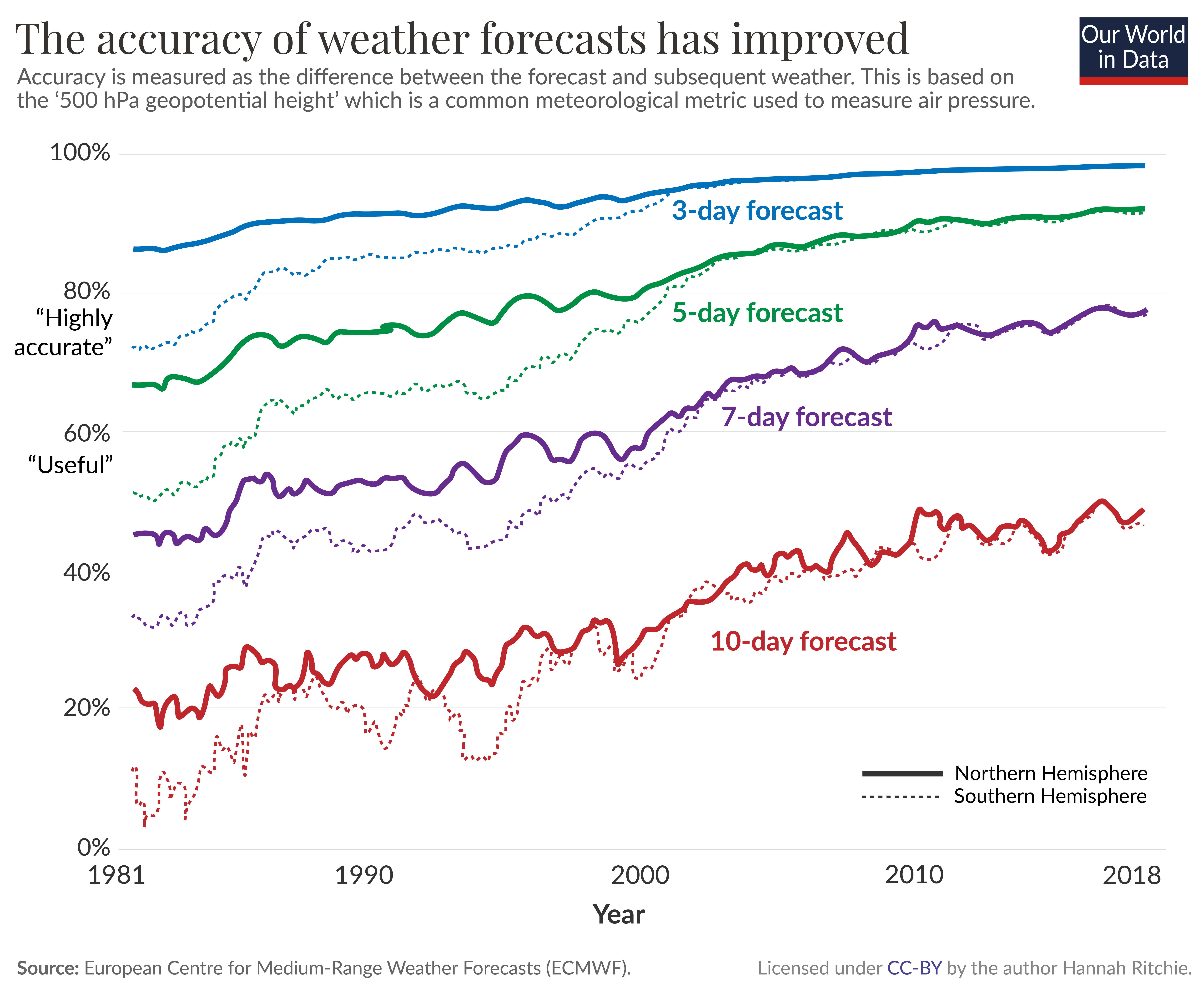

Weather predictions really are better than they used to be. (CC-BY: [Hannah Ritchie])These days, the NRO isn’t quite as secretive as it once was, and, in fact, much of the information for this post derives from two stories from their website. The NRO was also involved in the Manned Orbital Laboratory project and considered using Apollo as part of that program.

Weather forecasting, too, has gotten better. Studies show that even in 1980, a seven-day forecast might be, at best, 45 or 50% accurate. Today, they are nearly 80%. Some of that is better imaging. Some of it is better models and methods, too, of course.

However, thanks to one — or maybe a few — meteorologists, the Apollo 11 crew returned safely to Earth to enjoy their ticker-tape parades. After, of course, their quarantine.

hackaday.com/2025/09/25/spy-te…