GPS And Its Little Modules

Ever want to find your device on the map? Think we all do sometimes. The technology you’ll generally use for that is called Global Positioning System (GPS) – listening to a flock of satellites flying in the orbit, and comparing their chirps to triangulate your position.

The GPS system, built by the United States, was the first to achieve this kind of feat. Since then, new flocks have appeared in the orbit, like the Galileo system from the European Union, GLONASS from Russia, and BeiDou from China. People refer to the concept of global positioning systems and any generic implementation as Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS), but I’ll call it GPS for the purposes of this article, and most if not all advice here will apply no matter which one you end up relying on. After all, modern GPS modules overwhelmingly support most if not all of these systems!

We’ve had our writers like [Lewin Day] talk in-depth about GPS on our pages before, and we’ve featured a fair few projects showing and shining light on the technology. I’d like to put my own spin on it, and give you a very hands-on introduction to the main way your projects interface with GPS.

Little Metal Box Of Marvels

Most of the time when you want to add GPS into your project, you’ll be working with a GPS module. Frankly, they’re little boxes of well-shielded magic and wonder, and we’re lucky to have them work for us as well as they do. They’re not perfect, but all things considered, they’re generally pretty easy to work with.

GPS modules overwhelmingly use UART connections, with very few exceptions. There have been alternatives – for instance, you’ll find a good few modern GPS modules claim I2C support. In my experience, support for those is inferior, but Adafruit among others has sure made strides in making I2C GPS modules work, in case your only available interface is an I2C bus. The UART modus operandi is simple – the module continuously sends you strings of data, you receive these strings, parse them. In some cases, you might have to send configuration commands to your GPS module, but it’s generally not required.

Getting coordinates out of a GPS module is pretty simple in theory – listen for messages, parse them, and you will start getting your coordinates as soon as the module collects enough data to determine them. The GPS message format is colloquially known as NMEA, and it’s human readable enough that problems tend to be easy to debug. Here’s a few example NMEA messages from Wikipedia, exactly as you’d get them from UART:

$GPGGA,092750.000,5321.6802,N,00630.3372,W,1,8,1.03,61.7,M,55.2,M,,*76

$GPGSA,A,3,10,07,05,02,29,04,08,13,,,,,1.72,1.03,1.38*0A

$GPGSV,3,1,11,10,63,137,17,07,61,098,15,05,59,290,20,08,54,157,30*70

$GPGSV,3,2,11,02,39,223,19,13,28,070,17,26,23,252,,04,14,186,14*79

$GPGSV,3,3,11,29,09,301,24,16,09,020,,36,,,*76

And the great part is, you don’t even need to write comma-separated message parsers, of course, there are plenty of libraries to parse GPS messages for you, and a healthy amount of general software support on platforms from Linux to microcontroller SDKs. GPS modules are blindingly simple as far as interfacing goes, really. Feed your module 3.3 V or whatever else it wants, and it’ll start giving you location data, at least, eventually. And, a GPS module’s usefulness doesn’t even end here!

Bring Your Own Battery

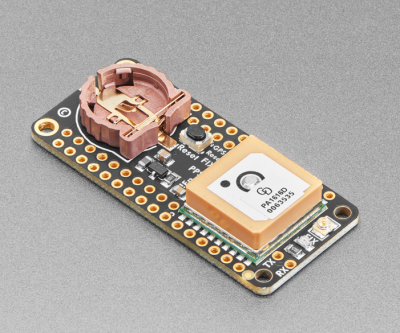

Even if your GPS board is super small, including a battery is always worthwhile. Picture from Adafruit

Have you ever seen a battery input pin on the module you’re using, or maybe even a battery socket? That’s for preserving the GPS satellite data and clock state while the module is not powered – making it that much faster to get your position after device bootup. This is known as “hot fix”, as opposed to a “cold fix”, when the module wakes up without any awareness which satellites it should be looking out for. Essentially, a backup battery cuts initial position lock time from minutes down to seconds, and it’s a must have for a battery-powered project.

Apart from getting the location fix way faster, a backup battery helps in more than one way. Because a GPS module’s inner workings depend so much on having a precise time source, you also get a rudimentary battery-backed RTC module, and with automatic time-setting directly from satellites, too! All in all, I do heavily recommend you make sure you wire up a backup battery to your GPS. Another nice thing GPS modules can provide you with is PPS – Pulse Per Second, an extremely precise 1Hz signal. There’s a number of specific things you can do with that, for instance, a pretty precise clock, but if you want more inspiration, our recent One Hertz Challenge has a large number of novel ideas that might just be a good fit for the PPS signal.

Let’s look at the “cold fix” scenario. No battery, or perhaps, powering up your module for the first time? GPS satellite signals have to be distinguished from deep down below the noise floor, which is no small feat on its own, and finding the satellites takes time in even favorable circumstances. If you can’t quite get your module to locate itself, leaving your house might just do the trick – or, at least, putting your board onto the windowsill. After you’ve done that, however, as long as you’ve got a backup battery going on, acquiring a fix will get faster. While the battery is present, your module will know and keep track of the time, and, importantly, which satellites to try and latch onto first.

The Bare Necessities

If you want to be able to wire up a GPS modem into your board anytime, you only really need to provide 4 pins on a pin header: 3.3 V, GND, and two UART pins. Frankly, most of the time, you’ll only need RX for receiving the GPS data, no configuration commands required, which means most of the time you can skimp on the TX pin. This is thanks to the fact that GPS as a technology is receive-only, no matter what your grandmother’s news sources might suggest. Apart from that, you might have to provide an antenna – most modems come with one integrated, but sometimes you’ll need to fetch one.

If the onboard passive antenna doesn’t help, the uFL is right there, waiting for your active antenna. Picture from Adafruit

GPS antennas are split into passive and active antennas – if you’ve seen a GPS module, you’ve likely seen active antennas, and they’re generally considered to be superiour. An active antenna is an antenna that includes an on-antenna amplifier chip, which helps filter out induced noise. In an average hacker project, an active antenna tends to be more workable, unless you’re making something that is meant to be in view of the sky at all times, for instance, a weather balloon. For such purposes, a passive antenna will work pretty well, and it will consume less power, too. Want to learn more? I’ve previously covered a blog post about modifying the internals of an active antenna, and it’s a decent case study.

If you’re putting a GPS module instead of using a standalone module, you won’t need to bring a power cable to the antenna, as power is injected into the same coaxial cable. However, you might need to add an extra inductor and a cap-two to support powering the antenna – watch out for that in the datasheet. Plus, treat antenna tracks with respect, and make sure to draw the antenna track with proper impedance. Also, remember to provide decoupling, and if you’re able at all, an RTC battery socket too – a CR1220 socket will work wonders, and the cells are cheap!

Increasingly Interconnected World

Recently, you’ll be getting more and more tech that comes with GPS included by default – it’s cheap, reasonably easy to add, very nice to have, and did I mention cheap? There’s also been a trend for embedding modules into 3G/4G/5G modem modules – most of them support things like active antennas, so, just wire up an antenna and you’ll know your coordinates in no time, perfect for building a tiny GSM-connected tracker for your valuables.

Want to learn more about GPS? It’s a marvellous kind of tech, and recently, we’ve been covering a fair few wonderful explainers and deep-dives, so check them out if you want to learn more about what makes GPS tick. Until then, you have everything you could want to slap GPS onto your board.

hackaday.com/2025/09/08/gps-an…