Ask Hackaday: Where Are All the Fuel Cells?

Given all the incredible technology developed or improved during the Apollo program, it’s impossible to pick out just one piece of hardware that made humanity’s first crewed landing on another celestial body possible. But if you had to make a list of the top ten most important pieces of gear stacked on top of the Saturn V back in 1969, the fuel cell would have to place pretty high up there.

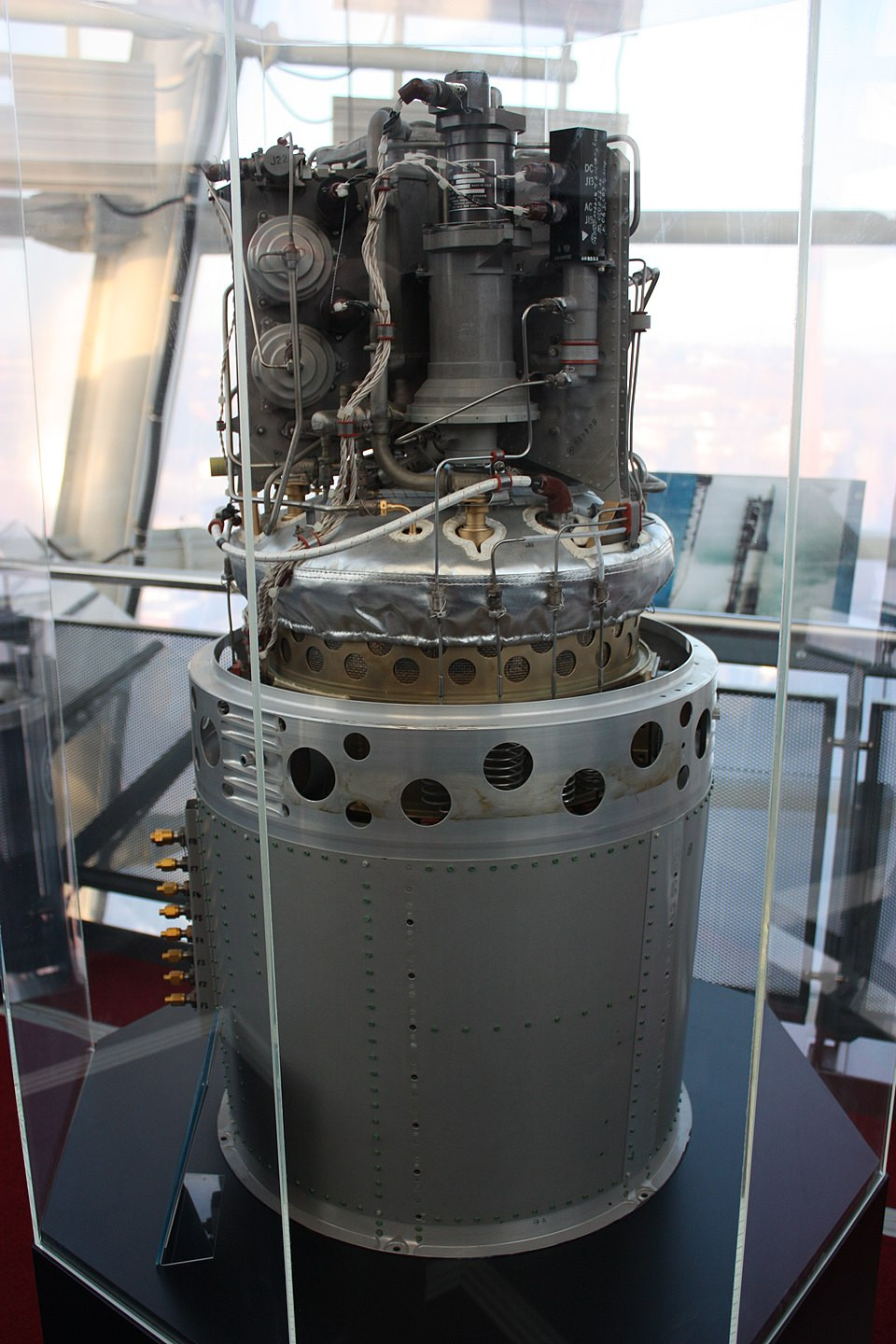

Apollo fuel cell. Credit: James Humphreys

Smaller and lighter than batteries of the era, each of the three alkaline fuel cells (AFCs) used in the Apollo Service Module could produce up to 2,300 watts of power when fed liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen, the latter of which the spacecraft needed to bring along anyway for its life support system. The best part was, as a byproduct of the reaction, the fuel cells produced drinkable water.

The AFC was about as perfectly suited to human spaceflight as you could get, so when NASA was designing the Space Shuttle a few years later, it’s no surprise that they decided to make them the vehicle’s primary electrical power source. While each Orbiter did have backup batteries for emergency purposes, the fuel cells were responsible for powering the vehicle from a few minutes before launch all the way to landing. There was no Plan B. If an issue came up with the fuel cells, the mission would be cut short and the crew would head back home — an event that actually did happen a few times during the Shuttle’s 30 year career.

This might seem like an incredible amount of faith for NASA to put into such a new technology, but in reality, fuel cells weren’t really all that new even then. The space agency first tested their suitability for crewed spacecraft during the later Gemini missions in 1965, and Francis Thomas Bacon developed the core technology all the way back in 1932.

So one has to ask…if fuel cell technology is nearly 100 years old, and was reliable and capable enough to send astronauts to the Moon back in 1960s, why don’t we see them used more today?

Fuel Cell 101

Before continuing to bemoan their absence from our everyday lives, perhaps it would be helpful to take a moment and explain what a fuel cell is.

In the most basic configuration, the layout of a fuel cell is not entirely unlike a traditional battery. You’ve got an anode that serves as the negative terminal, a cathode for the positive, and an electrolyte in between them. There’s actually a number of different electrolytes that can be used, which in turn dictate both the pressure the cell operates at and the fuel it consumes. But we don’t really need to get into the specifics — it’s enough to understand that the electrolyte allows positively charged ions to move through it, while negatively charged electrons are blocked.

The electrons are eager to get to the party on the other side of the electrolyte, so once the fuel cell is connected to a circuit, they’ll rush through to get over to the cathode. Each cell usually doesn’t produce much electricity, but gang a bunch of them up in serial and you can get your total output into a useful range.

One other element to consider is the catalyst. Again, the specifics can change depending on the type of fuel cell and what it’s consuming, but in general, the catalyst is there to break the fuel down. For example, plating the anode with a thin layer of platinum will cause hydrogen molecules to split as they pass through.

Earthly Vehicle Applications

So we know they were used extensively by NASA up until the retirement of the Shuttle back in 2011, but spacecraft aren’t the only vehicles that have used fuel cells for power.

The fuel cell powered Toyota Mirai, on the market since 2015.

There’s been quite a number of cars that used fuel cells, ranging from prototypes to production models. In fact, Toyota, Honda, and Hyundai actually have fuel cell cars available for sale currently. They’re not terribly widespread however, with availability largely limited to Japan and California as those are nearly the only places you’ll find hydrogen filling stations.

Of course, not all vehicles need to be filled up at a public pump. There have been busses and trains powered by fuel cells, but again, none have ever enjoyed much widespread success. In the early 2000s there were some experimental fuel cell aircraft, but those efforts were hampered by the fact that electric aircraft in general are still in their infancy.

Interestingly, outside of their space applications, fuel cells seem to have enjoyed the most success on the water. While still a minority in the grand scheme of things, there have been a number of fuel cell passenger ferries over the years, with a few still in operation to this day. There’s also been a bit of interest by the world’s navies, with both the German and Italian government collaborating on the development of the Type 212A submarine. Each of the nine fuel cells on the sub can produce up to 50 kW, and together they allow the submarine to remain submerged for weeks — a trick that’s generally only possible with a nuclear-fueled vessels.

Personal Power Plants

While fuel cell vehicles have only seen limited success, there’s plenty of other applications for the technology, some of which are arguably more interesting than a hydrogen-breathing train anyway.

At least for a time, it seemed fuel cells would have a future powering our personal devices like phones and laptops. Modern designs don’t require the liquid oxygen of the Apollo-era hardware, and can instead suck in atmospheric air. You still need the hydrogen, but that can be provided in small replaceable cylinders like many other commercially-available gases.

The peak example of this concept has to be the Horizon MiniPak. This handheld fuel cell was designed to power all of your USB gadgets with its blistering 2 watt output, and used hydrogen cylinders which could either be tossed when they were empty or refilled with a home electrolysis system. Each cylinder reportedly contained enough hydrogen to generate 12 watt-hours, which would put each one about on par with a modern 18650 cell.

The device made its debut at that the 2010 Consumer Electronics Show (CES), but despite contemporary media coverage talking about an imminent commercial release, it’s not clear that it was ever actually sold in significant numbers.

Looking at what’s on the market currently, a company called EFOY offers a few small fuel cells that seem to be designed for RVs and boats. They certainly aren’t handheld, with the most diminutive model roughly the size of a small microwave, but at least it puts out 40 watts. Unfortunately, the real problem is the fuel — rather than breathing hydrogen and spitting out pure water, the EFOY units consume methanol and output as a byproduct the creeping existential nightmare of being burned alive by invisible fire.

DIY To the Rescue?

If the free market isn’t offering up affordable portable fuel cells, then perhaps the solution can be found in the hacker and maker communities. After all, this is Hackaday — we cover home-spun alternatives for consumer devices on a daily basis.

Except, not in this case. While there are indeed very promising projects like the Open Fuel Cell, we actually haven’t seen much activity in this space. A search through the back catalog while writing this article shows the term “fuel cell” has appeared fewer than 80 times on these pages, and of those occurrences, almost all of them were discussing some new commercial development. There were two different fuel cell projects entered into the 2015 Hackaday Prize, but unfortunately both of those appear to have been dead ends.

So Dear Reader, the question is simple: what’s the hold up with mainstream fuel cells? The tech is not terribly complex, and a search online shows plenty of companies selling the parts and even turn-key systems. There’s literally a site called Fuel Cell Store, so why don’t we see more of them in the wild? Got a fuel cell project in the back of your mind? Let us know in the comments.