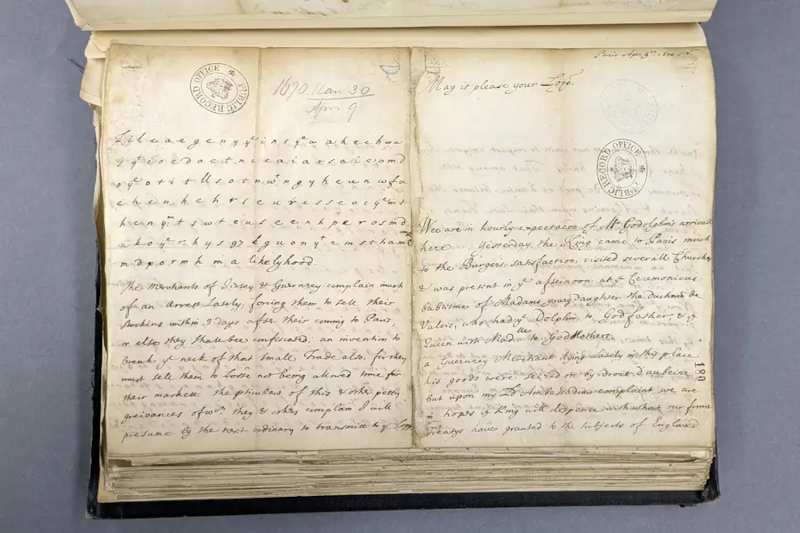

Decoding a 350 Year Old Coded Message

Usually, a story about hacking a coded message will have some computer element or, at least, a machine like an Enigma. But [Ruth Selman] recently posted a challenge asking if anyone could decrypt an English diplomatic message sent from France in 1670. Turns out, two teams managed it. Well, more accurately, one team of three people managed it, plus another lone cryptographer. If you want to try decoding it yourself, you might want to read [Ruth’s] first post and take a shot at it before reading on further here: there are spoilers below.

No computers or machines were likely used to create the message, although we imagine the codebreakers may have had some mechanized aids. Still, it takes human intuition to pull something like this off. One trick used by the text was the inclusion of letters meant to be thrown out. Because there were an odd number of Qs, and many of them were near the right margin, there was a suspicion that the Qs indicated a throw-away character and an end of line.

A further complication was that in 1670, there was no spell check. Or maybe the writer dropped some letters simply to thwart would-be decoders. The message was in columns that needed rearrangement, and some words like “THE” and “AND” are, apparently, abbreviated in the cipher. Some names and places had numeric codes and, despite novels and movies, are not decipherable without knowing the key or using some other knowledge that isn’t evident in the message.

If you do decide to try, the government has some (previously) classified code-breaking info to help you. If you want something even older, you can go back to the days of Mary, Queen of Scots.