Teletext Around the World, Still

When you mention Teletext or Videotex, you probably think of the 1970s British system, the well-known system in France, or the short-lived US attempt to launch the service. Before the Internet, there were all kinds of crazy ways to deliver customized information into people’s homes. Old-fashioned? Turns out Teletext is alive and well in many parts of the world, and [text-mode] has the story of both the past and the present with a global perspective.

The whole thing grew out of the desire to send closed caption text. In 1971, Philips developed a way to do that by using the vertical blanking interval that isn’t visible on a TV. Of course, there needed to be a standard, and since standards are such a good thing, the UK developed three different ones.

The TVs of the time weren’t exactly the high-resolution devices we think of these days, so the 1976 level one allowed for regular (but Latin) characters and an alternate set of blocky graphics you could show on an expansive 40×24 palette in glorious color as long as you think seven colors is glorious. Level 1.5 added characters the rest of the world might want, and this so-called “World System Teletext” is still the basis of many systems today. It was better, but still couldn’t handle the 134 characters in Vietnamese.

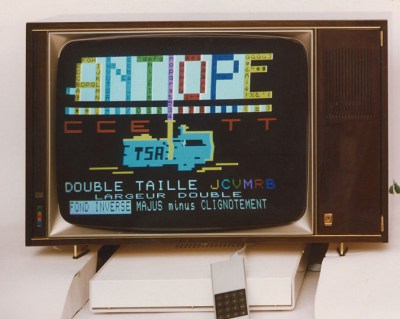

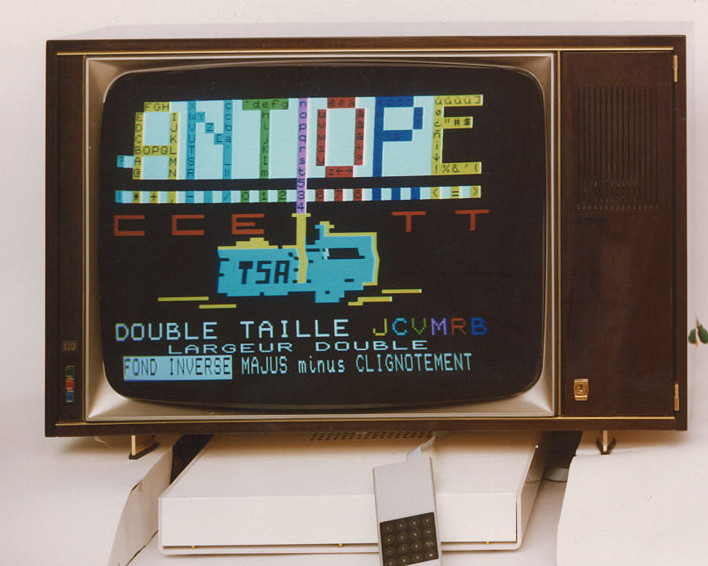

Meanwhile, the French also wanted in on the action and developed Antiope, which had more capabilities. The United States would, at least partially, adopt this standard as well. In fact, the US fragmented between both systems along with a third system out of Canada until they converged on AT&T’s PLP system, renamed as North American Presentation Layer Syntax or NAPLPS. The post makes the case that NAPLPS was built on both the Canadian and French systems.

That was in 1986, and the Internet was getting ready to turn all of these developments, like $200 million Canadian system, into a roaring dumpster fire. The French even abandoned their homegrown system in favor of the World System Teletext. The post says as of 2024, at least 15 countries still maintain teletext.

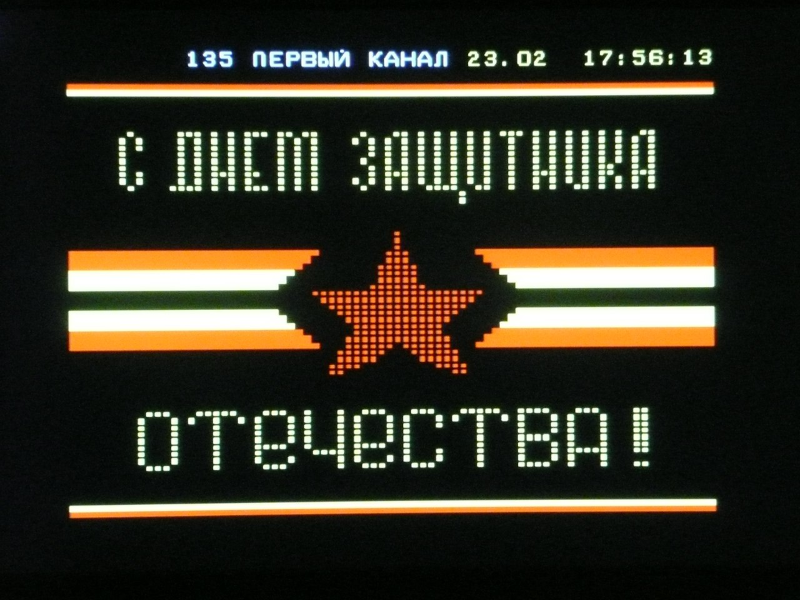

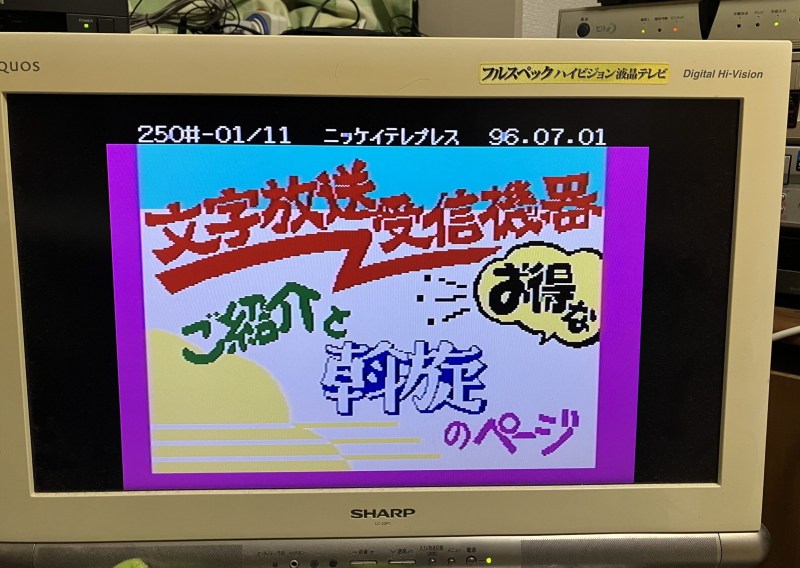

So that was the West. What about behind the Iron Curtain, the Middle East, and in Asia? Well, that’s the last part of the post, and you should definitely check it out.

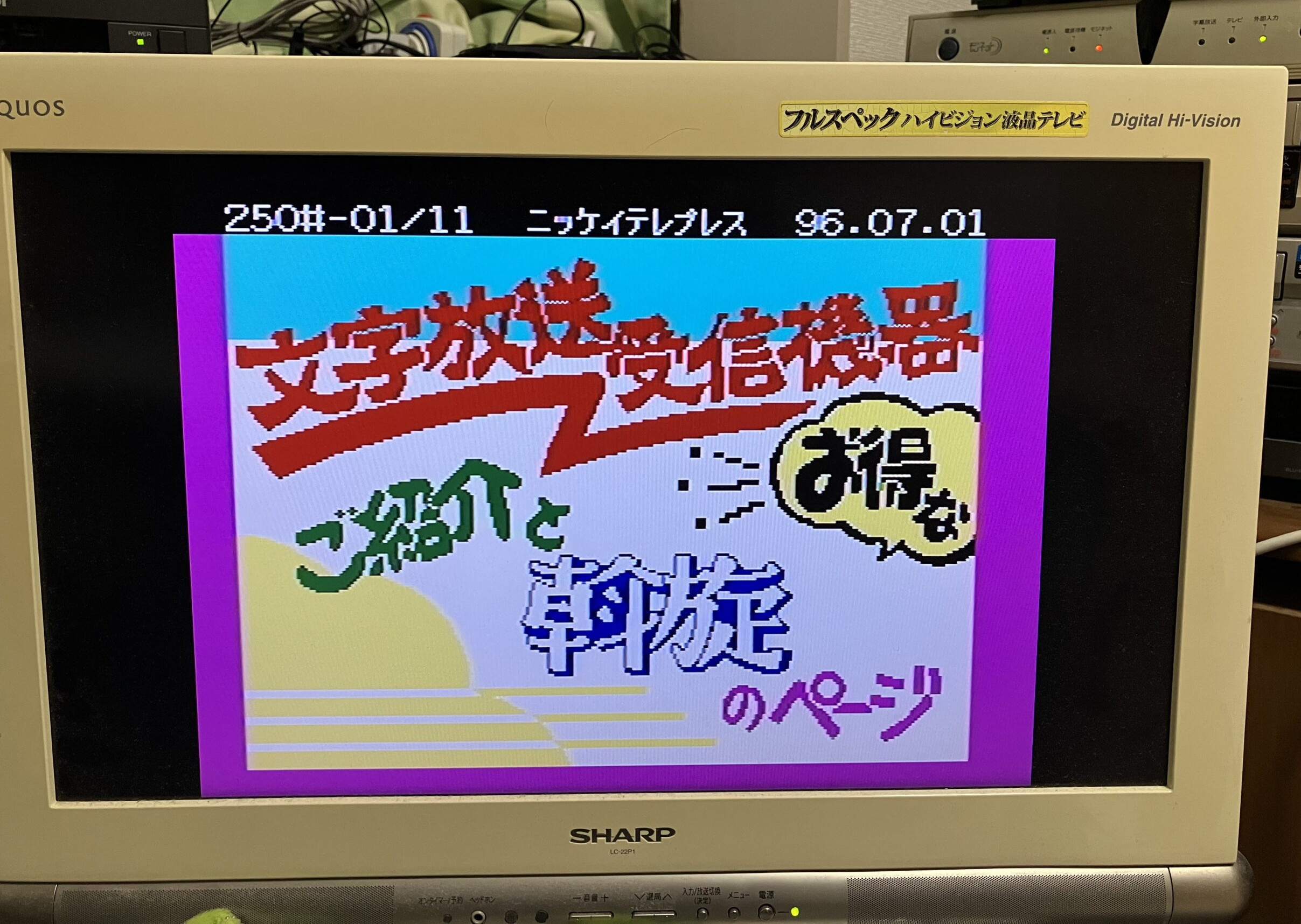

Japan’s version of teletex, still in use as of the mid-1990s, was one of the most advanced.

If you are interested in the underlying technology, teletext data lives in the vertical blanking interval between frames on an analog TV system. Data had page numbers. If you requested a page, the system would either retrieve it from a buffer or wait for it to appear in the video signal. Some systems send a page at a time, while others send bits of a page on each field. In theory, the three-digit page number can range from 100 to 0x8FF, although in practice, too many pages slow down the system, and normal users can’t key in hex numbers.

For PAL, for example, the data resides in even lines between 6 and 22, or in lines 318 to 335 for odd lines. Systems can elect to use fewer lines. A black signal is a zero, while a 66% white signal is a one, and the data is in NRZ line coding. There is a framing code to identify where the data starts. Other systems have slight variations, but the overall bit rate is around 5 to 6 Mbit/s. Character speeds are slightly slower due to error correction and other overhead.

Honestly, we thought this was all ancient history. You have to wonder which country will be the last one standing as the number of Teletext systems continues to dwindle. Of course, we still have closed captions, but with digital television, it really isn’t the same thing. Can Teletext run Doom? Apparently, yes, if you stretch your definition of success a bit.

hackaday.com/2025/08/15/telete…